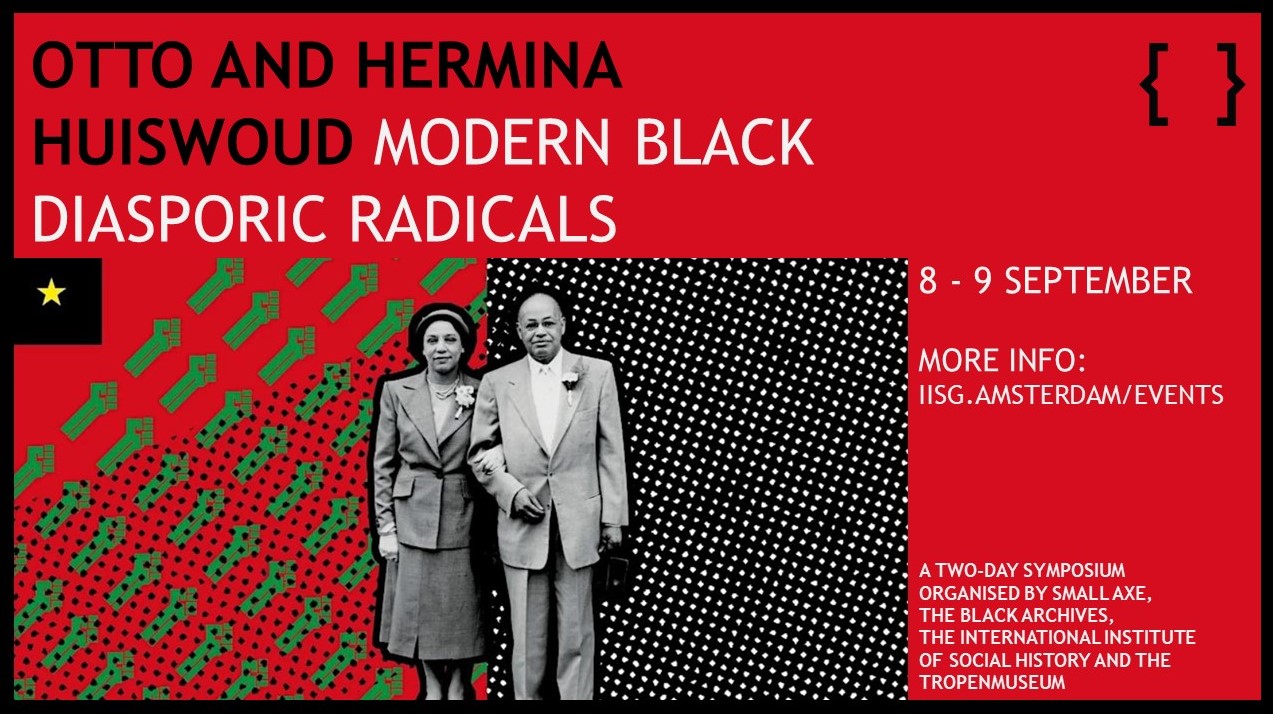

Symposium Report: Otto and Hermina Huiswoud: Modern Black Diasporic Radicals

The Symposium ‘Otto and Hermina Huiswoud: Modern Black Diasporic Radicals’ took place on the 8th and 9th of September in 2023 in Amsterdam. It was organized by Small Axe, The Black Archives, The International Institute of Social History (IISH) and the Research Center for Material Culture.

The topic of the symposium was Otto and Hermina Huiswoud, two international black radical thinkers and political organizers. The symposium brought together a group of international scholars, as well as an engaged public audience, to discuss questions to do with the Huiswouds’ relationship with communism and Pan-Africanism, their work for radical publications such as The Negro Worker and organizations such as the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers; their legacy in the Dutch Caribbean, and their archive at the Black Archives in Amsterdam.

Mayaki Kimba’s opening remarks set the stage for the symposium. Through his analysis of Hermina Huiswoud’s one-act play ‘Mrs. van Hogendorp’s Dilemma’ Kimba explored the depth and nuance of her anticolonial writing. Kimba argued that the Huiswouds were not the dogmatic foot soldiers that the anglophone literature often depicts them to be. Instead, the play reveals that Hermina’s ideas about race, class and decolonization are not limited to a reiteration of the communist party line.

The image of the Huiswouds as Comintern footsoldiers might partly be due to their insistence on class unity over racial unity as the solution to the black struggle. Otto Huiswoud famously argued this point against Marcus Garvey during a public debate in Kingston in 1929. However, to construct a binary between Garvey’s Pan-Africanism and Huiswoud’s communism might be an oversimplification. In his contribution to the workshop, Mano Delea pointed out that Otto Huiswoud was in fact supposed to speak at the fifth Pan-African congress before it was cancelled. This led Delea to ask what would have happened if he had spoken at the congress. In his paper ‘Traces of Pan-Africanism in the Works and Lives of Otto and Hermina Huiswoud’, Delea argues that Otto Huiswoud’s focus on decolonization and ending racist discrimination is in line with the core elements of Pan-Africanism.

Rather than constructing a binary between Pan-Africanism and communism, Leslie James’s contribution viewed them as overlapping antagonisms of black radicalism. Her paper ‘Beyond Antagonism: Otto and Hermina Huiswoud as Participants in Caribbean Anti-Colonial Radicalisms of the 1930s’ situated the Huiswouds in the history of 1930s black radicalism in the British Caribbean. James argued that the Negro Worker journal under their editorship displays ‘the dialogue of overlapping radicalisms’ of the 1930s Caribbean. Through a network of sailors and maritime workers, The Negro worker spread to the Caribbean and became part of its print ecology. James described how in this Caribbean print ecology texts from publications were cut out and these clippings were rearranged on a new page and recirculated. Through these clippings, texts written by Otto and Hermina Huiswoud became part of the Anti-colonial radical discourse in the Caribbean.

While their writings made it to the Caribbean, the Huiswouds spent the 1930s in Europe, where Otto was working as a professional revolutionary paid by the Comintern. Holger Weiss’ paper ‘Otto Huiswoud and the Demise of the Red Atlantic’ is the result of research at the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History into Otto’s work for Comintern. As the secretary of the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), Huiswoud worked to organize and agitate among black workers in Europe. Otto also became the editor of the Negro Worker, which served as the mouthpiece of the ITUCNW. Weiss argues that Huiswoud’s efforts were largely unsuccessful due to the fact that local authorities forced him to work underground. Furthermore, Huiswoud received little support from Moscow and was the victim of reorganizations and deprioritization which led to the eventual dissolving of the ITUCNW in 1938.

The contributions during the first sessions of the workshop situated the Huiswouds in British Caribbean radicalism, the Pan-Africanist movement and international communism. Guno Jones’ contribution to the symposium resituated the Huiswouds in the anticolonialism of the Dutch-speaking world. To this end, Jones compared Otto Huiswoud to Anton de Kom in his paper ‘Otto Huiswoud, Anton de Kom and the Broader Critical Caribbean Tradition. Cross-Caribbean Critical Interactions and the Limits of Liberation.’ The first similarity that stands out is that both Huiswoud and De Kom were Marxists and anticolonialists who fought for Surinamese independence. Jones argued that rather than comparing their relationships to communism and Pan-Africanism, we should view both De Kom and Huiswoud more holistically as anticolonial thinkers who incorporated different ideas in their struggle for black liberation. In addition to the similarities, Jones also drew attention to some important differences. The Huiswouds were tremendously cosmopolitan and had contact with a big international network. Anton de Kom, on the other hand, was largely unknown outside of the Dutch-speaking world. Perhaps the biggest difference between De Kom and the Huiswouds is in their legacy. After being a persona non grata for much of the second half of the 20th century, De Kom has in recent years become recognized and canonized as an important figure in Dutch history and Surinamese anticolonialism. In stark contrast to De Kom, the Huiswouds remain largely unknown figures, even to historians and members of the Surinamese community.

The second day of the workshop took place in the building of Vereniging Ons Suriname. This was very appropriate, given the Huiswouds’ founding role in this society of Surinamese people living in the Netherlands. The papers and discussion of the second day bridged the Huiswouds’ role as historical actors, and present day struggles for recognition. Mitchell Esajas's contribution to the symposium centered on their activities in the second half of the twentieth century. During this period the Huiswouds were active for the Vereniging Ons Suriname (VOS) the association for Surinamese people in Amsterdam. To Esajas the Huiswouds had a profound influence on the association. Otto and Hermina brought their international experience of political organizing to the association and served as mentors for its younger members. With Otto as chair from 1954 onwards, the association shifted to the left politically and started actively striving for Surinamese independence. Today the building of VOS houses the Black Archives: A community archive created in 2016 by a group of black students in Amsterdam. In 2017 The Black Archives opened an exhibition on the Huiswouds entitled ‘Zwart en Revolutionair’ or ‘Black and Revolutionary’.

The continued relevance of the Huiswouds also was the focus of Phaedra Haringsma’s paper ‘Silenced but not forgotten: on the Revolutionary contributions of Anton de Kom, Hermina and Otto Huiswoud.’ Haringsma argued for a more thorough inclusion of black thinkers like Otto and Hermina Huiswoud as well as Anton de Kom in International Relations theory. According to Haringsma, the Huiswouds served as a ‘link between the Dutch and Anglophone parts of the Black Atlantic’. Furthermore, Haringsma posited that the inclusion of the Huiswouds adds a new perspective to the relationship between black radicalism and Marxism. Hermina Huiswoud’s critique of George Padmore after his break with communism is especially relevant in this regard.

Margaret Stevens echoed Haringsma’s argument that the Huiswouds’ perspective on anticolonialism and anticapitalism is still relevant to the present day, especially in the Caribbean. In addition to her paper ‘From Primitive Accumulation to Cannibalized Dispossession: Standard Oil’s Jim Crow Lago Refinery on “One Happy Island’, 1925-1985”’, Stevens shared footage of her film titled ‘One Happy Island’. Stevens explained how American and Dutch multinationals cooperated in Aruba to extract its oil and in the super-exploitation of black Caribbean workers. In the process, these companies created a colony on the island with a strict racialized hierarchy. When the multinationals moved their focus to the middle-east they simply abandoned the oil refinery which is there to this day, leaving massive environmental damage in its wake.

The symposium brought together an international set of scholars each with a different perspective on the Huiswouds and their legacy. The event was public and attracted an engaged audience which enriched the discussion. Some among the audience had known Hermina Huiwoud, who outlived Otto by several decades. Unfortunately, Otto and Hermina destroyed many of their personal documents and letters, perhaps out of fear of persecution. Therefore the role of the archive or the lack thereof in the study of the Huiswouds was a recurring theme in almost every discussion. Another important question regarding the study of the Huiswouds concerns the implications of studying the Huiswouds together versus as individuals. Particularly a need for more research focused on Hermina Huiswoud was identified. Unlike Otto, she lived through a lot of the fallout of movements that they had been a part of before the war. The Huiswouds’ relationship to these international movements, particularly communism and Pan-Africanism was also a prominent theme throughout the symposium.

The Huiswouds might be a bridge between international black radicalism and the Dutch-speaking world, specifically by being a link between the British and the Dutch Caribbean. During the symposium, it became clear that there was and still is a divide between the two. Related questions arose regarding the differences and similarities between the Dutch and British colonial projects in the Caribbean and the forms of black radicalism that emerged in resistance to them.

Looking back at the lives of Otto and Hermina Huiswoud their legacy became an important theme during the symposium. Their legacy in international black radicalism but also their legacy in the Netherlands and Suriname in particular were discussed. During the discussions, this legacy was also connected to the trajectory of Surinamese decolonization and the suppression of leftist movements after its independence. The symposium was not limited to discussing the history of the Huiswouds but also touched on the continued relevance of the Huiswouds’ anti-colonial, anti-racist and anti-capitalist perspectives for the present-day.