‘Dachushka, do you live in freedom?’ Three generations of Belarusian protest by Eline Helmer

When I walk in, Natalia is sitting at the kitchen table in her daughter’s flat in Rotterdam, frantically writing. While Polina brings me tea and biscuits, her mother practices a poem she wrote in honour of the ‘Night of the Executed Poets’.

In the night of the 29th to the 30th of October 1937, over a hundred poets, writers and scientists were murdered in the forests of Kurapaty, just outside Minsk, Belarus. Between 1937 and 1941, thousands of people were killed here by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police[1]. Now Belarusians from all over the world, like Natalia, share poetry in an online initiative to remember.

‘We didn’t know each other until this summer’ is one of the often-cited slogans of the protests that started in the run-up to the presidential elections in August. This first line from a popular Russian love song[2] points to the feeling of newly acquired national consciousness. Yet it also paints a distorted picture, for the resistance against Lukashenka already encompasses three generations.

I met Polina and Natalia during the protests of the Belarusian diaspora in the Netherlands that started in June this year. Since the 9th of August, we have met in a different city each Sunday to draw attention to the falsified elections in Belarus and the violence that followed[3]. Thousands of people were arrested, hundreds were tortured and at least six people died. At this moment, thousands are still detained in terrible conditions. The Belarusians in the Netherlands are predominantly young people, some with small children. One of the regular guests during our protests is a two-year-old boy, who carries an enormous white-red-white flag in his small hands. When at one of those gatherings Polina and I talk about her politically active mother she laughs: ‘You should have seen my grandfather!’

Natalia, born in Nyasvizh, a provincial centre in the middle of Belarus, had a father who was ‘an exception in every possible way’. In a time when making a career without being a member of the Communist Party was impossible, Pavel Vasilevich threw his membership card on the table, in front of his boss. He didn’t agree with the latter’s order to inspect collective farms in rural Belarus. His ambition was to move to Minsk instead and ensure the best education for his two daughters. ‘Everyone had a full fridge at that time, while ours was empty’, says Natalia. ‘Everything had to be fresh. Back then nobody had heard of a healthy lifestyle, but my father copied yoga exercises from journals that he picked up at the Lenin library on his way from work. Sometimes I envied friends, who hosted dinners and had houses filled with guests. In our flat my dad would be alone in the living room, standing on his head.’

‘People say there was no opposition before this summer, while in fact there was. My father went to all meetings and called Lukashenka and his regime “Lukavina”. This is a play on the Russian “izluchina”, which refers to a bend in the river. Lukashenka takes Belarus, country of endless marshes, with him into the mud from which we can’t escape. Other politicians at the time thought he would soon be exposed, given his provincial manners and clumsy speeches. Ganchar, Zakharanka, Krasouski and Karpenka underestimated his cunningness: they all disappeared and nothing has been heard of them since.’ [4]

After research in 1988 had revealed the massive scale of the executions in Kurapaty, unofficial gatherings were organized to commemorate the victims of the terror.[5] Besides the night from the 29th to the 30th of October, the first Sunday of November was also incorporated. On that day, the much older Dzyady, of pagan origin, is celebrated, which literally means ‘forefathers’.

In the Night of the Executed Poets not only the poets were murdered; it was an attempt to murder the Belarusian language. No nation without a language, was the idea. At school Polina and Natalia studied Belarusian as a foreign language, just like English. And as with English, their knowledge of it did not reach beyond passive comprehension. This did not apply to Pavel Vasilevich. ‘When we came to visit him in the mid-1990s, he suddenly addressed us in Belarusian,’ says Natalia, ‘a language he continued to speak until his death.’

Approximately twenty years ago, Natalia met Henk in Minsk, where he was working for a Dutch company. They were among the few who took to the streets after the falsified elections in 2001. ‘I looked around me and was so disappointed: our voices had been stolen, we were lied to day and night, and still people did not get up from their couches. At that moment I decided for myself: I am going to turn this page. If people here don’t care, why should I?’ A few years later the couple moved to the Netherlands, together with Polina. Natalia considered it an opportunity: this way her daughter would get a chance to study abroad. Polina rapidly learned Dutch at her new school in Emmen. At home, they no longer talked about politics. Nevertheless, after her graduation Polina moved to The Hague to study European Studies and wrote her dissertation about Lukashenka. Now, after a short search, she retrieves the document in her flat in Rotterdam.

‘“Dachushka, daughter, do you live in freedom?” was the first thing my father used to ask me whenever I visited him in Minsk’, recalls Natalia. ‘Not “how was your journey?” or “are you hungry?” like other, normal parents. Freedom really was the most important thing for him. Only this summer I came to understand what he had meant all this time.’

Three months of uninterrupted protest may seem like a long time already, but actually today’s Belarusians are continuing a fight that their (grand)parents started years ago. The flag that the two-year-old boy carries through Dutch cities was sewn by a friend of his grandmother, the 73-year-old Nina Baginskaya[6]. Her perseverance – she has protested since 1988 – has turned her into an icon of the current protests.

On the 6th of September, just before his 93th birthday, Pavel Vasilevich passed away. ‘I wish he could have seen all this, and that he could have joined the March of the Pensioners, like Nina Baginskaya.’ Natalia spreads her arms. ‘“Now I can die”, he would have said. But that is not how it went.’ During the last three years of his life, Natalia’s father was often confused. Polina doubts whether her grandfather realized what was happening this summer. Yet in his final two weeks, once in a while he would suddenly get up from his bed and stride across the room, saying he wanted to write. Natalia thinks that despite his old age and clouded thoughts he felt the sense of urgency. ‘As if he understood that now it’s now or never.’

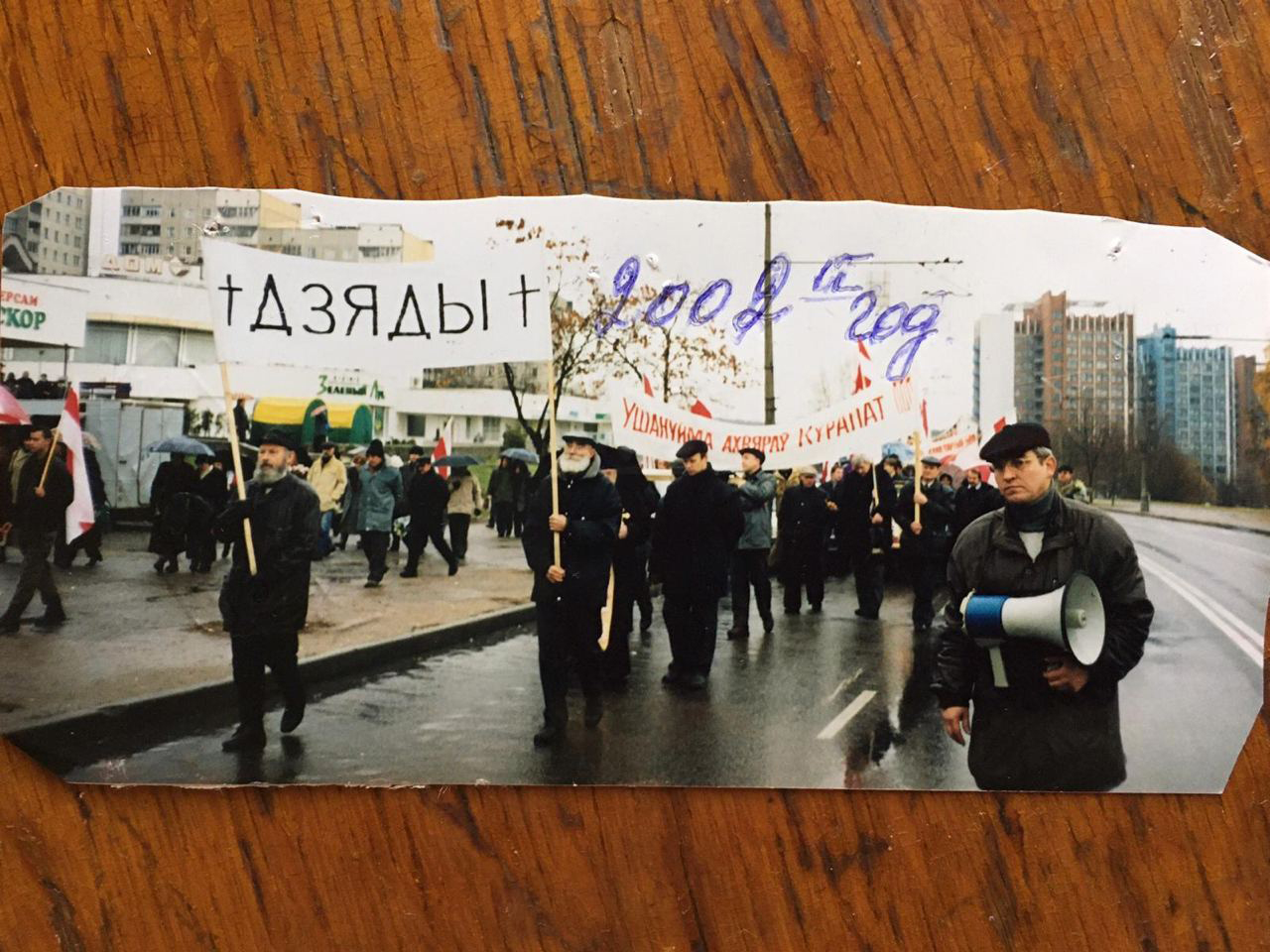

Image: Dzyady in 2002: Pavel Vasilevich on the left, with beard and banner ‘Dzyady’. In the background red-white-red flags of the opposition, as well as a banner reading ‘Honour for the victims of Kurapaty’.

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zj6TnsD2zyo

[3] http://spring96.org/en/publications

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jul/20/ameliagentleman