‘Moderne slavernij’: waarom is onvrije arbeid zo hardnekkig? door Jan Lucassen

Al sinds 2020 trekken mensenrechtenorganisaties aan de bel over de abominabele omstandigheden en de rechteloosheid van arbeidsmigranten die betrokken zijn bij de bouw van stadions en andere infrastructurele werken in Qatar in verband met het WK voetbal dat op 20 november dit jaar begint. Deze extreme vorm van vrijheidsbeperking van arbeiders, dikwijls ‘moderne slavernij’ genoemd, is een hardnekkig verschijnsel. Maar om te begrijpen waarom, ondanks de formele en wereldwijde afschaffing van slavernij, allerlei soorten en gradaties van onvrije arbeid zo hardnekkig voortbestaan, moeten we verder terug in de tijd. Want alleen vanuit een historisch perspectief kunnen we begrijpen waarom veel mensen en partijen – en niet alleen hebzuchtige werkgevers – grote belangen hebben bij het voortbestaan van onvrije arbeid.

The IISH and the Pandemic by Aad Blok

The Covid pandemic and its consequences for public and private life have been talked and written about endlessly in the past year, from a great many different perspectives and views.

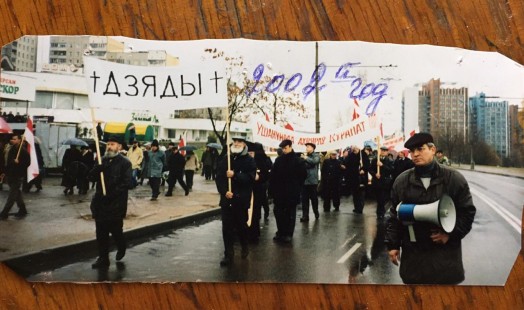

‘Dachushka, do you live in freedom?’ Three generations of Belarusian protest by Eline Helmer

When I walk in, Natalia is sitting at the kitchen table in her daughter’s flat in Rotterdam, frantically writing. While Polina brings me tea and biscuits, her mother practices a poem she wrote in honour of the ‘Night of the Executed Poets’.

The PKI archives and the need for more inclusive descriptions by Rika Theo

But it seems you do not realize, Meneer Pangemanann, that your report is not for the general public. Only a very few people in the Indies and in the world have read and studied it … You will never know, and indeed do not need to know, who else has read it.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer, House of Glass (New York, 1992), p. 24.

Black Lives Matter in global history by Leo Lucassen

The Black Lives Matter protests in the United States resonate strongly throughout the world. Not only in Europe, but also in Seoul, Monrovia, Sydney, Rio de Janeiro, and even in war-torn Idlib in Syria, where a mural honouring George Floyd has been painted. But the protests have also generated opposition. Critics of the protests often point at other forms of racism, for example in Asia and Africa, asking ‘what about racism in other parts of the world?’ Although in itself a legitimate question, it is used as a rhetorical strategy to trivialize widespread institutional racism against people of colour, especially pertaining to descendants of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic world.

Spanish flu: How the world changed in the aftermath of the 1918-1919 pandemic by Touraj Atabaki

“One fateful night in the summer of 1918, with the Great War about to end, in the heart of the darkness three menacing horsemen each in possession of a whip and sword silently breached the walls and entered the town. One was called Famine, another Spanish Influenza and the other Cholera. The poor, the old and the young fell like autumn leaves ravaged by the assaults of these ruthless horsemen.”

'Pandemie legt arbeidsverhoudingen bloot', door Gijs Kessler

De coronacrisis legt meedogenloos het onderscheid bloot tussen zelfstandigen en mensen die werken in dienstverband. De sluiting van de horeca, het verbod op het uitoefenen van contactberoepen en het afgelasten van alle grote evenementen raken ondernemers en zelfstandigen rechtstreeks in hun portemonnee, terwijl de meeste mensen met een dienstverband hun salaris voorlopig gewoon doorbetaald krijgen, of er nu werk is of niet.

Comparing Covid-19 and the Spanish Flu: Not so much the ‘Great Leveler’ but particularly hitting the poor, by Ulbe Bosma

“The Coronavirus pandemic will cause famine of biblical proportions”, the UN warned on Tuesday 21 April. It immediately made a headline in The Guardian and other media followed suit. The COVID-19 epidemic not only has grave consequences for societies with fragile health care systems, for many countries it comes after locust swarms have battered their crops.

![Illustratie: Groep arbeiders op collectief stukloon in de baksteenindustrie, Noord-Duitsland, 1903. [Bron: Landesarchiv NRW Abt. OWL, Detmold (Germany), D 75 Nr. 2670.]](/files/styles/12x7_524w/public/2020-05/KesslerLucassen_Ill8.2.jpg?itok=r1Il4wBs)